After weeks of anticipation, I’m finally in Salvador! E aqui é tudo beleza. This is my first trip to Brazil on business, and I’m finding that working in a bilingual, binational team is incredibly exciting, but it does come with its own frustrations as we adjust to the pace and ways of doing things in Brazil (the project unfolds in slow motion, as everything takes at least twice as long).

After weeks of anticipation, I’m finally in Salvador! E aqui é tudo beleza. This is my first trip to Brazil on business, and I’m finding that working in a bilingual, binational team is incredibly exciting, but it does come with its own frustrations as we adjust to the pace and ways of doing things in Brazil (the project unfolds in slow motion, as everything takes at least twice as long).

My colleagues and I are staying at a beautiful resort hotel right on the beach, near the Itapuã neighborhood. The sea is green-blue and warm, though the waves are strong. As the lifeguard told me, O mar aqui é meio bravo. Down the road is Vinícius de Morães’ old house, which has been converted into a hotel. We’ve been eating moqueca every other night, and the nights in between we’re eating picanha.

But, this being my first time in Bahía, I truly realize now how northern Brazil might as well be a different country from southern Brazil. The city of Lauro de Freitas, where we are staying, is basically one giant favela with a commercialized highway running through the middle.

All around is the familiar Brazilian urban fabric, a barely constrained chaos draped over a gorgeous landscape of white sand dunes and scrubby hills. Favela houses of cinder block mix with upscale furniture stores and ugly high rise condos. Teenage boys ride their bikes against the flow of traffic, at night, on a highway where trucks scream by at 90 km/h, while entire families wait for breaks in the traffic to dash across three lanes. Sometimes it seems like everything, *everything*, is made of concrete here – even the fence posts. Concrete walls are everywhere, plastered with the names of petista candidates. It’s all very chaotic, but also mesmerizing.

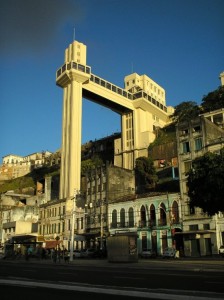

We took a trip into the historic center of the city, which is almost surreal. The way Salvador interacts with its environment reminds me a lot of Rio; you could almost say that the two are close cousins. A fine place to start is the lower part of the city near the waterfront. From here, your eyes are immediately drawn to the towering cliff of rock on which the cidade alta is built, a vertical rise made even more dramatic by the tall buildings packed together right along its edge. To top it all off, there is the Elevador Lacerda, a strikingly beautiful Art Deco column bridging the vertical space between the two cities, like nothing I have ever seen. I had looked at pictures of the elevador, but they did not prepare me for staring up at the real thing – or for the vista at the top. The other attraction in the cidade baixa is the old Mercado Modelo, a bustling two-story craft market. This view from the mercado, looking up at the elevador, is the image of Salvador that I will most remember. It’s just so Brazilian – the chaotic mix of old and new, all of it dingy yet full of pulsing life, all built atop breathtaking natural beauty. Brazilian cities are truly like no other.

You pay 15 centavos (!) to ride the elevator to the top, and when the doors open, suddenly you are perched high above the dingy buildings of the cidade baixa, and there is the blue green bay spread out before you. Walk down the street a short way, and now you are in the Pelourinho, the colonial tourist district that is a bit like Casco Viejo in Panama City, only in much better repair. As you wander the steep cobblestone streets, you walk past multicolored rowhouses, ornate 17th and 18th century churches, and lots and lots of street vendors.

It is impossible to be in the center of Salvador and not imagine how it looked when the first Portuguese ships arrived on a brisk Bahian breeze nearly 500 years ago. The Pelourinho is the very epicenter of slavery in Brazil. All around you are reminders of Brazil’s brutal history – the square where 3 million enslaved Africans first set foot on land after a grueling sea journey, the baroque churches where crooked priests and bishops conducted their clandestine business, and where Brazil’s upper crust paid to have their family’s bones interred, the sanctuaries gilded with half a ton of Mineiro gold and Potosí silver (all mined by slaves), the hollow wooden statues of the saints into which was secretly placed many more tons of gold, for safe shipment across the sea to the king of Portugal. Like Gustavo Freyre smuggling his crystal meth in buckets of chicken batter marked with UV fluorescent stars, only some of the saints contained gold. You would know them by the misplaced details: the wrong number of beads on a rosary, an extra knot on a sash.

You feel that there are a lot of ghosts in Salvador, with a lot of stories to tell.

It is also not an easy place to be a tourist. All kinds of people approach you – children patting their bellies in mock hunger; women from the church of Senhor do Bomfim wanting to give you a blessing, who absolutely will not leave you alone until you give them a few coins; aggressive street merchants. It was a good opportunity for me to remember how to tell people, with varying degrees of forcefulness, to buzz off (perhaps a post on this is in order). After wandering around the Pelourinho for a bit, we must have inadvertently crossed the invisible line separating the area patrolled by the tourist police from the rest of the city, because no sooner had we turned down the street than a man blocked our path. “Perigoso!” he shouted, motioning for us to turn back. Although I usually take such warnings with a grain of salt, there was an urgency in his voice that told me we should follow his advice. We turned around and headed back to the elevador.

The other parts of Salvador are equally strange and beautiful. Brazilian cities have their own unmistakeable geography, and Salvador is no exception. Once you get away from the beach, it’s largely a city of hills. This makes transportation difficult, as the main thoroughfares are restricted to the winding valleys between the hills; the traffic is usually terrible. As you drive into the central, more middle class part of the city, you find yourself driving down wide highways running through cramped valleys, threading between steep hills topped with towering hi-rise edifícios.

The geography of Brazil’s large cities is the clearest reflection of the stark social stratification. If you’re poor, you live in the huge favelas that ring the suburbs. If you’re middle class, you live in an apartment high above the ground, closer to the city center. Only the upper middle class and the wealthy live in communities resembling those in North America, with large houses and yards and driveways, and even those communities tend to be gated, with high walls and armed guards.

What we’ve been seeing over the last 10-15 years in Brazil is a huge segment of people moving from the favelas into the lowest strata of the middle-class — perhaps being able to afford a small apartment, or drive a car instead of riding the bus. These new middle class families would still be called “poor” in the U.S., but in Brazil it is a marked step forward. Yet it’s obvious, traveling around Salvador, that the north of Brazil still has a lot of catching up to do. Here in Bahía, it seems like they’re still 20 years behind the southern states – and the favelas are not emptying out any time soon.

Salvador, in particular, suffers from a lack of urban planning — to say nothing of the short-sightedness of the dictatorship that filled Brazil’s cities with densely packed soviet-style high-rises . The high-rises tend to be built on hills alongside wide highways, sealed off from the fabric of the city and nearly inacessible by foot. But in other parts of Salvador, the apparent lack of zoning laws creates a dynamic urban fabric – a new urbanists’ dream of mixed-use neighborhoods bustling with pedestrians.

Even amidst all the chaos, or maybe because of the chaos, there is definitely something intoxicating about Salvador, and I’m looking forward to getting to know the city better in the remaining time I have here. And eating more moquecas.

(By the way, I was surprised to find that Lonely Planet does not offer a standalone guide to Salvador or Bahia. And I found the Salvador information in their guide to all of Brazil to be thin. So I looked around and found a Bradt guide called Bahia: The heart of Brazil’s northeast which I’m happy to say has lots of detailed information on Salvador, as well as the beach towns up and down Bahia’s coast. And you can tell that the English author is a true Brazilophile by the amount of cultural and historical information he has packed in :-)