This is the fourth in a series of posts on Tropicália and the Brazilian counterculture under the dictatorship, based on my study with Dr. Talia Guzman-Gonzalez at the University of Maryland, who has kindly helped me to edit my Portuguese writing.

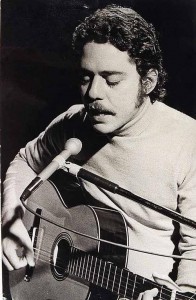

Chico Buarque é conhecido como o mestre lírico e a conciência moral da música brasileira nos anos 70. As letras dele são estudadas e analizadas por sua estrutura poética, duplo sentido, e jogo de palavras.

Chico Buarque é conhecido como o mestre lírico e a conciência moral da música brasileira nos anos 70. As letras dele são estudadas e analizadas por sua estrutura poética, duplo sentido, e jogo de palavras.

Antes de gravar as músicas mais marcantes da sua carreira, ele era amado pelos fãs da MPB. A maioria das músicas dele eram inspiradas pela bossa nova e samba. Venceu o Segundo Festival de Música Popular Brasileira com A Banda, uma bossa nova.

Mas ao longo dos anos 60, ele voltou a ser cada vez mais político nas composições. Eventualmente, ele chamou a atenção dos censores. Naquela época, era necessário que os artistas entregassem novos músicas, livros e filmes ao Departamento de Ordem Política e Social (DOPS) para obtenir permissão a lançá-los. Os censores exigiam frequentemente que ele retirasse ou substituisse várias frases ‘inaceitaveis’, como por exemplo em Partido Alto. Isso não dava para Buarque, e ele se encontrava obrigado a criar codenomes — Julinho da Adelaide e Leonel Paiva — para gravar sua música na forma em que ele quisesse. Um agente da ditadura descobriu a artimanha e começou a requer que as artistas entregassem documentos de identificação (Penedo do Amaral 2012). Buarque foi interrogado várias vezes.

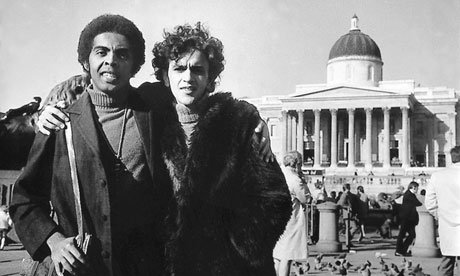

In 1968, como nós já discutimos, a situação no Brasil piorou com o decreto de AI-5. Em 1969, Emílio Médici assumiu a presidência e isso deu início ao período mais difíceis para as artistas (1969-1974). Enquanto Caetano Veloso e Gilberto Gil passaram seu exílio em Londres, Chico Buarque se exilou na Itália, onde tinha passado uns anos com a família quando era criança (o pai era o grande historiador Sérgio Buarque de Holanda). Ele passou o ano de 1970 lá, e voltou para o Brasil em 1971. Ao voltar, ele experimentou uma abordagem mais criativa: ao inves de usar codenomes, ele compôria músicas de duplo sentido — inocente na superfície, mas com crítica aguda por baixo. Disfarçada assim, a mensagem de protesto escaparia o olho do censor.

In 1968, como nós já discutimos, a situação no Brasil piorou com o decreto de AI-5. Em 1969, Emílio Médici assumiu a presidência e isso deu início ao período mais difíceis para as artistas (1969-1974). Enquanto Caetano Veloso e Gilberto Gil passaram seu exílio em Londres, Chico Buarque se exilou na Itália, onde tinha passado uns anos com a família quando era criança (o pai era o grande historiador Sérgio Buarque de Holanda). Ele passou o ano de 1970 lá, e voltou para o Brasil em 1971. Ao voltar, ele experimentou uma abordagem mais criativa: ao inves de usar codenomes, ele compôria músicas de duplo sentido — inocente na superfície, mas com crítica aguda por baixo. Disfarçada assim, a mensagem de protesto escaparia o olho do censor.

Apesar de Você

Apesar de Você é assim. À primeira vista, parece uma simples samba-canção sobre um amor caido aos pedaços. De fato, foi inicialmente aprovada pelos censores e distribuida às lojas. Mas uma matéria num jornal sugeriu que o você na letra podia ser uma referência ao Presidente Médici. DOPS trouxe Buarque para o escritório para exigir que ele explicasse o sentido da música. Logo depois o álbum foi censurado. Daí, Chico teve muitas músicas dele rejeitadas. Uma foi Calabar, que simbolizou a ditadura por meio dos colonizadores hollandeses.

Hoje você é quem manda

Falou, tá falado

Não tem discussão

A minha gente hoje anda

Falando de lado

E olhando pro chão, viu

Você que inventou esse estado

E inventou de inventar

Toda a escuridão

Você que inventou o pecado

Esqueceu-se de inventar

O perdão

Apesar de você

Amanhã há de ser

Outro dia

Eu pergunto a você

Onde vai se esconder

Da enorme euforia

Como vai proibir

Quando o galo insistir

Em cantar

Água nova brotando

E a gente se amando

Sem parar

Quando chegar o momento

Esse meu sofrimento

Vou cobrar com juros, juro

Todo esse amor reprimido

Esse grito contido

Este samba no escuro

Você que inventou a tristeza

Ora, tenha a fineza

De desinventar

Você vai pagar e é dobrado

Cada lágrima rolada

Nesse meu penar

Apesar de você

Amanhã há de ser

Outro dia

Inda pago pra ver

O jardim florescer

Qual você não queria

Você vai se amargar

Vendo o dia raiar

Sem lhe pedir licença

E eu vou morrer de rir

Que esse dia há de vir

Antes do que você pensa

Apesar de você

Amanhã há de ser

Outro dia

Você vai ter que ver

A manhã renascer

E esbanjar poesia

Como vai se explicar

Vendo o céu clarear

De repente, impunemente

Como vai abafar

Nosso coro a cantar

Na sua frente

Apesar de você

Amanhã há de ser

Outro dia

Você vai se dar mal

Etc. e tal

Também em 1971, Buarque gravou o álbum Construção. Este álbum contem algumas das suas músicas mais políticas e críticas da ditadura: Cotidiano, Construção, Samba de Orly, e Deus lhe Pague. Nessas, ele empregou duplo sentido e jogo de palavras para evadir o olho dos censores.

Ambos Cotidiano and Construção tratam das brutalidades diárias da vida urbana sob a ditadura. A industrialização rápido do chamado Milagre Brasileiro enriqueceu os já ricos, mas trouxe pouco para os trabalhadores que vieram em bando para as cidades grandes para trabalhar nas fábricas e construções de concreto. Para eles, o progresso era esmagador.

Cotidiano

Todo dia ela faz tudo sempre igual:

Me sacode às seis horas da manhã,

Me sorri um sorriso pontual

E me beija com a boca de hortelã.

Todo dia ela diz que é pr’eu me cuidar

E essas coisas que diz toda mulher.

Diz que está me esperando pr’o jantar

E me beija com a boca de café.

Todo dia eu só penso em poder parar;

Meio-dia eu só penso em dizer não,

Depois penso na vida pra levar

E me calo com a boca de feijão.

Seis da tarde, como era de se esperar,

Ela pega e me espera no portão

Diz que está muito louca pra beijar

E me beija com a boca de paixão.

Toda noite ela diz pr’eu não me afastar;

Meia-noite ela jura eterno amor

E me aperta pr’eu quase sufocar

E me morde com a boca de pavor.

Cotidiano se trata de temas de submissão à opressão, a monotonia da vida diária, e a falta de agentividade (impotência). Nessa música vimos como a falta de poder pode esmagar a vontade de resistir, até que as pessoas se acostumem com a impotência. Assim, a submissão à autoridade pode se tornar um hábito.

Mais uma vez, Buarque encaixa a ditadura na forma de uma mulher, neste caso a esposa do narrador. Ao longo da música, que se move da manhá até a noite, ela o decepciona com cordialidades e confissões de amor banais que soam falsas por serem repetidas do mesmo maneira dia após dia. Estas me lembram dos palavrãos de ordem e propagandas divulgados pelos governos militares ao longo do século vinte — uma forma de “Fique calma e siga em frente!“.

A rotina do casal é refletida na estrutura das estrofes, que têm todas a mesma forma. A música, por sua vez, consiste de uma série de acordes em queda que repete, estrofe a estrofe, sem o alívio de um refrão ou ponte. A única interrupção nesse padrão é o momento de suspensão nos fins dos estrophes, em que o ritmo muda e o tempo parece a ser pendurado, suspenso, com a esperança de algum novidade que nunca vem, só a próxima estrofe. Quando Buarque atinge o fim da letra, ele volta ao início e o ciclo se repete de novo, até que a música desvanece. Não tem início ou fim, nem fuga dessa rotina.

Na superfície, a casal tem um relacionamento tradicional — o homem trabalha fora da casa, a mulher o espera em casa. Mas por baixo não tem nenhuma paixão, sentimento sincero, ou novidade, só atos mecânicos. Sorrir. Beijar. Despedir da manhã. Cumprimentar à noite. Na vida deles, tudo é pré-determinado; nenhum dos dois tem agentividade ou controle sobre a vida. Também não há espaço para individualidade ou personalidade. Eles estão presos numa rotina interminável. Dessa forma, Buarque exprime o sentimento de impotência da vida sob a ditadura.

Isso se vê até na gramática dos versos. O homem é sempre o objeto passivo das ações do mulher. Ela me sacode, me beija, me espera, me aperta, me morde. Finalmente, na terça estrofe, vemos uma centelha de espera — ele começa a exercitar sua agentividade e se torna sujeito dos próprios ações: Todo dia eu só penso em poder parar / meio-dia eu só penso em dizer não / depois penso na vida de levar. Pela primeira vez, ele considera a possibilidade do seu próprio poder. Pensa no futuro. Mas logo ele apaga estes pensamentos perigosos, seja de um sentimento de desespero ou de pavor. É mais fácil simplesmente voltar ao presente (me cale com boca de feijão) e continuar a sobreviver. Isso é um retrato fascinante do jeito em que as ditaduras exercita controle sobre os cidadãos.

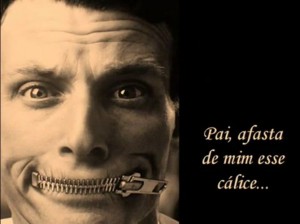

Cálice

Pai! Afasta de mim esse cálice

Pai! Afasta de mim esse cálice

Pai! Afasta de mim esse cálice

De vinho tinto de sangue

Father! Take this cup away from me

Father! Take this cup away from me

Father! Take this cup away from me!

This cup of blood red wine

Como beber dessa bebida amarga

Tragar a dor e engolir a labuta?

Mesmo calada a boca resta o peito

Silêncio na cidade não se escuta

De que me vale ser filho da santa?

Melhor seria ser filho da outra

Outra realidade menos morta

Tanta mentira, tanta força bruta

How can I drink this bitter drink

Drown the pain and swallow the toil?

Even shut, my mouth rests on my chest

Silence in the city cannot be heard

What is it worth to be the child of a saint?

Better to be the child of some other

Some other reality less dead

So many lies, so much brute force

Como é difícil acordar calado

Se na calada da noite eu me dano

Quero lançar um grito desumano

Que é uma maneira de ser escutado

Esse silêncio todo me atordoa

Atordoado eu permaneço atento

Na arquibancada, prá a qualquer momento

Ver emergir o monstro da lagoa

How difficult it is to wake up silenced

If in the silence of the night I hurt myself

I want to give an inhuman scream

Which is one way to make yourself heard

This silence stuns me

Stunned, I remain alert

In the bleachers, expecting at any moment

To see the lagoon monster emerge

De muito gorda a porca já não anda (Cálice!)

De muito usada a faca já não corta

Como é difícil, Pai, abrir a porta (Cálice!)

Essa palavra presa na garganta

Esse pileque homérico no mundo

De que adianta ter boa vontade?

Mesmo calado o peito resta a cuca

Dos bêbados do centro da cidade

The pig is so fat it no longer walks (Shut up!)

The knife is so used it no longer cuts

How difficult it is, Father, to open the door (Shut up!)

This word caught in my throat

This Homeric liquor (?) in the world

Which ? to have good will

Even shut up my mouth rests on the cuckoo

Of the drunks downtown

Talvez o mundo não seja pequeno (Cale-se!)

Nem seja a vida um fato consumado (Cale-se!)

Quero inventar o meu próprio pecado (Cale-se!)

Quero morrer do meu próprio veneno (Pai! Cale-se!)

Quero perder de vez tua cabeça! (Cale-se!)

Minha cabeça perder teu juízo. (Cale-se!)

Quero cheirar fumaça de óleo diesel (Cale-se!)

Me embriagar até que alguém me esqueça (Cale-se!)

Perhaps the world isn’t so small (Shut up!)

Nor is life a consumed fact (Shut up!)

I want to invent my own sin (Shut up!)

I want to die of my own venom (Shut up!)

I want to lose your head (Shut up!)

My head to lose your judgement (Shut up!)

I want to smell diesel fumes (Shut up!)

To get drunk until someone forgets me (Shut up!)

O exemplo mais famoso do duplo sentido na obra do Buarque, “Cálice” é uma poderosa canção de protesto, e também a música dele que trata de forma o mais direita do tópico de censura. Embora ele a gravasse com Milton Nascimento, foram Buarque e Gilberto Gil que escreveu a letra e música. Abre com um cântico de igreja a capella, estabelecendo um contexo religioso para a letra que segue. A linguagem religiosa é com certeza uma capa que esconde o sentido político, mas será que ela também seja uma crítica da igreja católica que era cúmplice às brutalidades da ditadura? (em grande parte — claro que tinham padres na esquerda bem como na direita, mas como uma instituição mundial, a igreja era cúmplice por causa do seu silêncio).

Buarque e Nascimento se revezam ao cantar cada estrofe. O refrão é cheio de imagens cristãs, mas as estrofes trazem com seu tema a dor de ser silenciado, a necessidade de ser escutado, e o tratamento violento de quem se manifestar contra o estado. Tem muitos símbolos da voz como objeto corporal: uma boca calada, os atos de beber e engolir, palavras presas na garganta.

Cálice, claro, pode significar uma taça para vinho, ou a órdem Cale-se! Os gritos do Chico funciona como contraponto às estrofes, a voz dos censores. A apresentação de Cálice por Buarque e Nascimento em 1973 no show televisado Phono foi uma das apresentações mais memoráveis da época da ditadura. Proibidos de cantar a letra “subversiva”, eles cantarolam a melodia, se tornando cada vez mais corajosos. Enfim Chico grita “Cale-se!” várias vezes em sucessão, até que alguém desligue o microfone. Ele o tamborila com o dedo. “Tem som?” pergunta à plateia. Tem algo profundo nesse censura de uma música sobre a censura.

A linha Quero inventar meu próprio pecado se trata da linha da Apesar de Você em que Buarque canta Você que inventou pecado.

As linhas Quero morrer do meu próprio veneno e Quero cheirar fumaça de óleo diesel se referem a Stuart Angel Jones, um militante do grupo revolucionário MR-8. Ele foi preso pela polícia militar e torturado com boca colada para a válvula de escape de um veículo. Assim, a polícia o envenenou com as fumaças e o matou. Essa tórtura representa a censura na sua forma mais violento e final.

Devido ao conteudo subversivo, DOPS não deu permissão para Buarque e Nascimento gravarem Cálice até 1978.

Construção

Amou daquela vez como se fosse a última

Beijou sua mulher como se fosse a última

E cada filho seu como se fosse o único

E atravessou a rua com seu passo tímido

Subiu a construção como se fosse máquina

Ergueu no patamar quatro paredes sólidas

Tijolo com tijolo num desenho mágico

Seus olhos embotados de cimento e lágrima

Sentou pra descansar como se fosse sábado

Comeu feijão com arroz como se fosse um príncipe

Bebeu e soluçou como se fosse um náufrago

Dançou e gargalhou como se ouvisse música

E tropeçou no céu como se fosse um bêbado

E flutuou no ar como se fosse um pássaro

E se acabou no chão feito um pacote flácido

Agonizou no meio do passeio público

Morreu na contramão atrapalhando o tráfego

Amou daquela vez como se fosse o último

Beijou sua mulher como se fosse a única

E cada filho seu como se fosse o pródigo

E atravessou a rua com seu passo bêbado

Subiu a construção como se fosse sólido

Ergueu no patamar quatro paredes mágicas

Tijolo com tijolo num desenho lógico

Seus olhos embotados de cimento e tráfego

Sentou pra descansar como se fosse um príncipe

Comeu feijão com arroz como se fosse o máximo

Bebeu e soluçou como se fosse máquina

Dançou e gargalhou como se fosse o próximo

E tropeçou no céu como se ouvisse música

E flutuou no ar como se fosse sábado

E se acabou no chão feito um pacote tímido

Agonizou no meio do passeio náufrago

Morreu na contramão atrapalhando o público

Amou daquela vez como se fosse máquina

Beijou sua mulher como se fosse lógico

Ergueu no patamar quatro paredes flácidas

Sentou pra descansar como se fosse um pássaro

E flutuou no ar como se fosse um príncipe

E se acabou no chão feito um pacote bêbado

Morreu na contra-mão atrapalhando o sábado

Em Construção, vemos mais uma vez um homem comum, da classe operária, levando uma vida sem esperança ou agentividade. Este homem trabalha numa daquelas altas construções de concreto que foram construidas por todo o Brasil nos anos 70s.

Até mais do que em Cotidiano, vemos estrofes em que a repetição é o principal elemento organizador. Cada linha começa com um verbo no preterito; assim a vida dele é narrada através uma série de ações. Cada linha termina com uma palavra proparoxítona, criando uma poesia rítmica. No fim de cada estrofe, o tempo aumenta e a repetição mais intensa.

Quando ele cai da construção, batendo no chão com violência, o único efeito é a atrapalhação de trânsito; é uma morte sem sentido, pelo menos na media em que a sociedade se importa.

No segundo e terceiro versos acontece algo interessante. A última palavra de cada linha é substituida por uma de outra estrofe, e assim a letra fica atrapalhada. As substituições se tornam cada vez mais surrealistas. O absurdo dos versos destaca o absurdo da morte do homem numa sociedade em que a morte é coisa cotidiano.

* Foram recentemente descobridos milhares de documentos que o DOPS manteu durante a ditadura, pertencendo às investigações de 45 mil pessoas, incluindo o ex-presidente Lula e Ché Guevara. Será que tem documentos sobre Chico também?

Hurray for a new version (2.0) of

Hurray for a new version (2.0) of