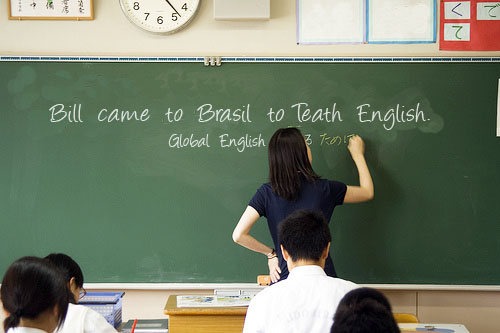

It’s a popular thing for us Americans to do nowadays: live abroad for a year, or two, or five. Where do you want to go exactly? I dunno…someplace exotic… South Korea, maybe, or Cambodia, or Peru, or Brazil. Now the big question: how are we going to get by? Oh you know… we could always teach English.

Well, why not? There’s a great demand for English education in pretty much everywhere in the world, and as native speakers we’ve got all the qualification we need.

Or do we?

A reader left a comment that got me thinking about all those programs that hire American students with no teaching experience and no knowledge of the local language.

“I visit Hacking Portuguese regularly, and find it more helpful than polling online Brazilian friends because the lessons come from the POV of a native English speaker. It’s nearly impossible to communicate the basis for some of the questions generated when learning Portuguese to a native because there’s no common context. Which prepositions to use with which verb is an excellent example of this. In fact I asked a friend from Rio this morning for some general guidelines on the use of por and para, and he said it was too complicated to explain, and that reading Portuguese books and articles would provide the best method for understanding the uses. It’s reasonable advice, but I would like to become fluent sometime this decade!”

And here is how I responded:

Thank you Brett! I completely agree that in some ways, it is easier to learn Portuguese from a native English speaker who can explain things in reference to our shared native language. As good as my tutors and professores have been, sometimes they don’t know how to explain things the way that my brain wants, or they don’t understand the nuances of the problem I am grappling with. That’s why I endorse programs like Tá Falado, which combine the expertise of native Portuguese speakers and a native English teacher who can anticipate the trouble spots.

I also think it’s naive to assume that just because you speak a language, you’re capable of teaching it to someone who doesn’t. There are so many things you need to know in order to teach. The grammar of the language you’re teaching (we often have grammatical blinders on when it comes to our native language. Having faint recollections of grammar class in school does not help you understand the complexities of how your language really works). The grammar of your students’ native language. An understanding of teaching pedagogy and second-language acquisition.

You have to be reasonably fluent in the native language of your students. And you have to have studied the grammar of the language you are teaching inside and out. Only then can you teach the language in a way that will make sense to your students.

Learning a language is a process of forming a model of your target language. At first it starts out as a very rough model that is a mish-mash of elements of your native language(s) and elements of your target language, but you gradually refine it until it looks more and more like the target language. The process of refining it happens by making mistakes. You make a statement in your target language. Then maybe your teacher corrects part of what you have said. And based on that correction, you see that part of your model is incorrect, so you adjust your model accordingly.

Linguists call this mental model an interlanguage. It’s your best approximation of how the target language operates, and it allows you to make predictions about what is right or wrong in the language, even about things that you haven’t explicitly been taught.

Now, to be an effective teacher, you need to have a good idea of what your students’ interlanguage looks like. And you need to know what your students starting assumptions are. How do they model the language in their heads? Where are they likely to make mistakes? Which things will be challenging for them to understand? Because the interlanguage is based in part of the native language of the student, you absolutely must have a good command of that language.

Students are continually making comparisons between the target language and their native language. In English, you do this, but in Spanish, you do this. The knowledge is stored as a mapping from one language to the other. The job of a good teacher is to help students internalize those comparisons until they no longer need the native point of reference. But you must understand what that point of reference is!

My point is two-fold. If you are considering teaching English abroad, you will be a much better teacher (and probably earn more money) if you have a) spent a good amount of time grappling with the complexities of your students’ native language b) gotten some training on how to teach English. The Teach English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) certification is offered by many companies and requires only a few months to complete.

But my other point, perhaps more controversial, is that we should think about how fluent-but-non-native speakers can be effective teachers as well. Learning from someone who has already spent years studying your target language can be extremely valuable. Ideally, you would want a team consisting of a native speaker and a fluent (but non-native) speaker. I think this is why programs like Tá Falado are so successful – you get all the benefits of hearing native speakers, but also the wisdom of Orlando Kelm’s experience with Portuguese.

I agree that being a native speaker does not on its own make a good language teacher. My boss, however, would not agree. He is from the UK and opened an English school in Brazil where he hires only native English speakers (usually traveling 20-somethings). I walked in one day with a resume that included a B.A. in English Lit and minimal foreign language tutoring experience–basic Spanish, not English as a foreign language–and he very quickly concluded that I was an expert. Even though I’d never studied Portuguese a day in my life (and I’m still very much in the process of learning).

When I expressed my uncertainty to my boss about being thrown headfirst into teaching without any training, he said I was overthinking it and to just wing it. Although the approach was, let’s say, “refreshing” for me (I tend to over-plan), I hardly felt qualified. Four months later, I don’t feel much different.

And it’s because the things you cited in your blog post are true; that to be a good teacher, among other things you not only need to know your own language’s grammar inside and out, but you need to be able to explain it in a way that reaches your students (i.e., having more than a passing familiarity with their first language).

In the case of my boss, I can see that he has a business to run and needs a steady stream of cheaply paid teachers; and that on the other side of it, young travelers jump at the chance to get a “tax-free,” reasonably well-paying job. But I believe my boss’ faith in the “you’re-native-and-therefore-an-expert” mentality extends beyond his business model. I know this because he has entrusted me with teaching English to his own 12-year-old Brazilian-raised daughter–with the high stakes of trying to be admitted to an American school. He gave that job to me specifically, above other (albeit only slightly) more experienced teachers at our school. And it’s because I also happen to have a B.A. in English Lit.

I think this mentality is pervasive (hence your blog post), even beyond teaching English. For example, I have a friend from Spain who, before moving to Brazil, studied a bit of Portuguese in Madrid. Her teacher was a native Brazilian Portuguese speaker who, in my friend’s opinion, seemed to have no other qualifications. As a student, she found this frustrating. And as paid English teacher these days, I sometimes feel like a fraud, in spite of my boss’ insistence to the contrary.

In the end, I attempt to remedy this guilt by doing my best to learn how to teach English grammar, which for me means blundering through some lessons and making a lot of mistakes along the way. I’m getting better.

I’m also trying to learn Portuguese, although the “Ta Falado” approach seems like a much more ideal and innovative solution. I hope to improve and I’m considering getting TEFL certified (thanks for the tip; I wasn’t aware of the exam). And thanks for the blog post; it makes me feel more justified in my belief that it takes much more than a native tongue to be a successful teacher!