This is the first in a series of posts on Tropicália music and the Brazilian counterculture under the dictatorship, based on my study with Dr. Talia Guzman-Gonzalez at the University of Maryland. Some posts are in English and others are in Portuguese. I have provided my own English translations for all the lyrics quoted, including a few songs that I have not found in translation elsewhere.

Divino Maravilhoso – Gal Costa & Caetano Veloso

“I sang with all the fury and strength that I had in me. Half of the audience stood up to boo. The other half applauded ferociously.”

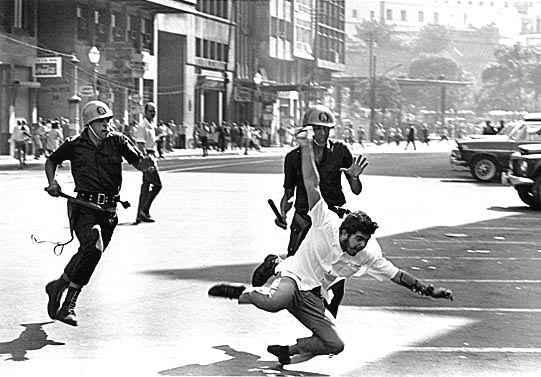

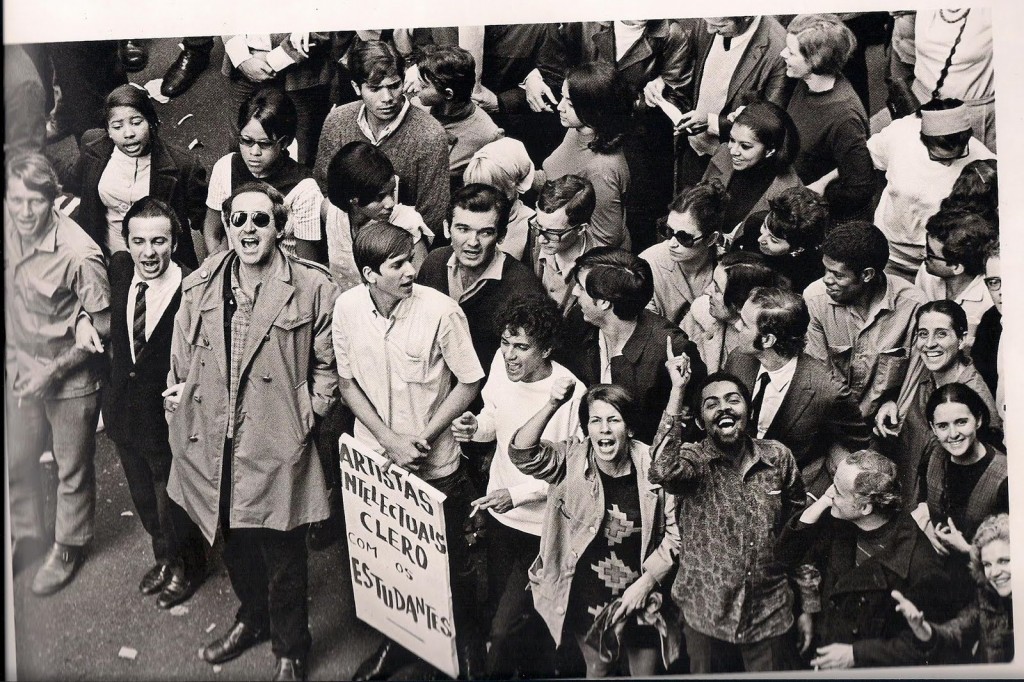

1968 was an intense year of protest and repression in Brazil. Four years after the military took power in a devastating coup, signs of organized resistance were beginning to stir on the Left. Following the example of French students in Paris, leftist students in Brazil led the first large street protests in São Paulo and Rio. But in the fall, the dictatorship cracked down on the protestors with a brutal new law called AI-5. It repealed habeas corpus, dissolved the legislative and judicial branches of government, and made mass protest illegal. AI-5 effectively ended organized public resistance to the dictatorship. In response, the left wing moved underground and fractured into dozens of groups, some advocating armed revolution.

In the midst of all this, music was one of the few forms of expression that opponents of the regime had left — the censors hadn’t yet begun to silence and exile musicians. Bossa nova, born in the late 1950s when Brazil was the cosmopolitan country of the future, was now seen as passé by many young people; the sentimental lyrics were too apolitical and introspective for the times. But new genres of music were stirring: Jovem Guarda artists assimilated the British and American rock n’ roll sound, iê-iê-iê musicians exploited the youth culture of the Beatles, and música popular brasileira (MPB) artists argued for a more nationalistic expression of popular music. Both rock and pop were coming into their own in a uniquely Brazilian way.

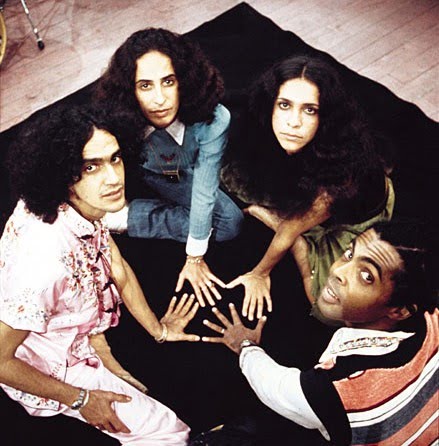

The young Bahians: Caetano Veloso, Maria Bettânia, Gal Costa, Gilberto Gil

Enter a group of young Bahían musicians — among them, Gal Costa the bossa nova singer. Like many of her contemporaries, Gal’s fascination with music began with João Gilberto and bossa nova. She and Caetano Veloso released an album of bossa nova tunes in 1966. But in 1968, she found herself as part of the emerging force of tropicália. Love and revolution were in the air, and she wanted to do something a bit…different.

That brings us to this exquisite, seminal moment of Brazilian television: Gal Costa’s 1968 appearance on Festival de Record. Televised festivals like this one were hugely popular as a way for Brazilians to tune into popular music, and they ultimately became the stage for the young Bahians to articulate a new vision of Brazilian music.

In the video, the audience immediately knows something is up when Gal, who had previously been known for her tasteful bossa nova renditions, comes out on stage rocking an afro and a huge mirrored necklace dangling from her neck. At first, she appears a bit timid and startled by the audience’s intense reaction. She lights into Divino Maravilhoso (Divine Marvelous), a rock song penned by Caetano Veloso and one of the most overtly political anthems of late sixties tropicália. During the first verse she stands fairly reservedly, and sings:

Atenção ao dobrar uma esquina

Uma alegria, atenção menina

Você vem, quantos anos você tem?

Atenção, precisa ter olhos firmes

Pra este sol, para esta escuridão

Watch out,

Whenever you round a corner,

Or a happiness – Watch out young lady!

“Come here! How old are you?”

Watch out,

You need to have steady eyes

For this sun, for this darkness

But this is not Chega de Saudade. This is a new Gal Costa.

The opening lines evoke the oppressive “papers please” climate of intimidation that has seized Brazil since the coup. Next Gal sings of the dual spirit of the times — one of danger, but also of countercultural experimentation:

Atenção

Tudo é perigoso

Tudo é divino maravilhoso

Atenção para o refrão

Watch out,

Everything is dangerous

Everything is divine marvelous

Watch out for the chorus! [or, Pay attention to the chorus!]

Perhaps only the English word “groovy” captures the psychedelic, everything’s-cool-man spirit conveyed by the phrase divino maravilhoso. With most forms of political resistance outlawed, only cultural resistance remained, in the form of experimentation with drugs, challenging gender and sexual norms, and of course, pop music. Music that might contain political or social messages if you’re reading between the lines, if you’re paying atenção to the chorus.

That last line — Atenção pra o refrão! — is so very meta. Look out, here comes the chorus. Gal had just recently seen some footage of Janis Joplin and she decided to incorporate elements of Janis’ style into this performance: Every time she gets to that line she shouts it defiantly and emits a Joplin-esque scream before launching into the chorus:

É preciso estar atento e forte

Não temos tempo de temer a morte

You gotta be alert and strong

We don’t have time to fear death

The nucleus of the song is the repeated slogan Atenção!, which could be read as both a warning to beware of danger (“Watch out!”) and as a piece of advice on how to survive in the military era (“Pay attention!” or “Listen up!”). Pay attention, because music is not just for entertainment: music has social and political signification. And in the era of AI-5, music has to be a bit more subtle about its subtext if it’s going to pass by the censors. Atenção is therefore both a call to action and a declaration of the importance of artists in the new political environment.

By the second verse, Gal starts to gain more confidence:

Atenção para a estrofe e pro refrão

Pro palavrão, para a palavra de ordem

Atenção para o samba-exaltação

Watch out for the verse and the chorus

for the curse words, for the slogans

Watch out for the samba-exaltação

Tropicalist artists shared a suspicion not just of the military dictatorship, but of the leftists and communists as well. These groups had their own rigid ideologies, dictates and artistic imperatives that the young Bahians resisted. (Caetano returns to this theme in Estrangeiro: pay attention to the old man and the young girl, speaking as one voice, and who they might symbolize). In this verse, Gal and Caetano urge the listener to beware of sloganeering from the left, both the curse words (palavrão) and the political slogans (a palavra de ordem).

Caetano’s lyrics refer here to the samba-exaltação, a patriotic type of samba that was used as a tool of nationalist propaganda by the regime of Getúlio Vargas in the 1930-40s. The song that defined this genre was Ary Barroso’s well-known carnaval samba Aquarela do Brasil. Although it is now considered a classic of samba and MPB, Aquarela might have been forgotten were it not for the 1942 Disney cartoon Saludos Amigos which brought it to worldwide attention. The appeal of this song stretches across genres and national boundaries; over the years it’s been transformed into a jazz standard, a disco hit, a protest song, an MPB standard, a Kate Bush cover from Terry Gilliam’s film Brazil, a Ney Matogrosso cover, an R&B hit, and most recently re-popularized in the US as a sort of global lounge music by Pink Martini. (There’s a whole paper waiting to be written, tracing the strange evolution of Aquarela in Brazil and the US. And there’s another paper to be had in the work of Norman Gimbel and Bob Russell, who created the English lyrics to songs like Aquarela and Girl from Ipanema, often changing their meanings and even the melodic line substantially to suite the tastes of American audiences).

I see these sambas-exaltações as a sort of ufanismo, a term used to describe the glowing letters of the early Portuguese explorers who described the abundance of Brazil in hyperbolic terms; it later came to refer also to the patriotic slogans of the dictatorship era (“Brazil – Love It or Leave It”, “Forward Brasil!”) which were meant to inspire nationalist sentiment and quell dissent. So by warning people to beware of the samba-exaltação, Gal is saying to beware of government propaganda.

Atenção para as janelas no alto

Atenção ao pisar o asfalto, o mangue

Atenção para o sangue sobre o chão

Watch out for the high-up windows

Watch out when you step on the asphalt, the swamp

Watch out for the blood on the ground

More images of a police state: the “high-up windows” from which the military police would keep an eye on protests in the streets of São Paulo; the blood of protestors and dissidents on the ground. The lyrical boldness here is almost brazen. This is one of the most overt songs of political resistance in the Tropicália cannon. After AI-5, there would be no more songs like this for many years. Messages of protest were still there, but they became more subtle and allegorical.

Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil and other artists march in support of the student movement. The sign says “Artists, intellectuals and clergy with the students”.

What I love about Gal in this video is the way her performance becomes increasingly less restrained as she sucks up the energy from the audience — both the adulation and the boos (you can’t hear the booing, but according to her there was plenty of it). Her pre-chorus shouts become louder and more violent, her intonation wavers, her movements become more aggressive. By the end she seems physically exhausted, exuberant — and covered in streamers.

But you can also detect, at least in the beginning, a bit of nervousness. You can tell that this performance style is new for her, and that she’s not quite sure how it will go over in front of an audience on national television.

I’ll leave you with this snippet of a 2005 interview, in which Gal explained the genesis of this life-changing performance:

“At that time I was completely immersed in the tropicalist environment. We spoke of nothing but the new movements that were emerging in the world. Gil listened to Hendrix all day long. I couldn’t get Janis Joplin out of my head. That sound, that raspy voice, took me in and created in me the need to do something different from what I believed, different from everything I had done up till then and from how I understood music at the time… I needed to do something to express myself, to put out there what I was feeling with force, with attitude — and, to be honest, to call attention to myself…

I came across Divino Maravilhoso, a song that really grabbed me. Caetano invited me to sing it at the Festival do Record, and Gil proposed to do the arrangement. Gil was astute enough to ask me how I wanted to sing it. I explained that I wanted to sing in a new way, explosive, out of this world. I wanted to show that there was another woman inside me. Another Gal besides the one who would sit on a stool and quietly sing bossa nova. I wanted to sing explosively! Really put it out there. So Gil went and made the arrangement for Divino Maravilhoso.

When Caetano saw me step onto the stage covered in baubles, with mirrors dangling from my neck, and that afro haircut, he nearly died of shock. He hadn’t known about any of this. He hadn’t heard Gil’s arrangement — nothing. I sang with all the fury and strength that I had in me. Half of the audience stood up to boo. The other half applauded ferociously. A man in front of me shouted insults. It was then that I felt a still greater strength that flung me against him. I sang directly to him: É preciso estar atento e forte, não temos tempo de temer a morte! I sang with such force and such violence that the poor guy shut up and shrank away, and disappeared inside himself. It was the first time that I felt what it was like to dominate an audience. A furious audience! At that time of political polarization, music was the only form of expression. It awoke passions, wars. I walked away from Divino Maravilhoso strengthened, grown up. I think that on that night I took the stage as a teenager, and left as a woman. Suffering, bruised — but victorious.”

– my translation, from Gal Costa’s website

You can hear the influence of Divino Maravilhoso in the wonderfully off-the-wall Meu Nome é Gal, from her 1969 album Gal, in which she collaborated with early Brazilian rockers Erasmo Carlos and Roberto Carlos. Gal screams and shouts atop searing electric guitars and a psychadelic orchestral arrangement – a defiant statement of the new direction that Brazilian pop music would take in the 1970s.

Language Notes

The lyrics to Divino Maravilhoso are pretty simple, so there’s not too much to say. I did learn the expression dobrar uma esquina = to go round a corner. Dobrar means to fold, so it makes sense. The ao in ao dobrar uma esquina is a way of saying “upon”, as in “Upon rounding a corner…”. You always stick it right before a verb in infinitive form:

Ao chegar no portão, ligue para o porteiro. (Upon arriving at the gate, call the doorman)

Two good words to know when talking about lyrics (a letra) are a estrophe (verse) and o refrão (chorus).

And after listening to Divino Maravilhoso a few times, you’ll never forget how to say “Watch out for” something – it’s Atenção para…

Atenção pro carro! (Watch out for the car!)

If you’re interested in learning more about the Tropicália movement, I recommend two books. Brutality Garden is a very readable survey of the movement that will help you understand its roots and analyze individual songs. Caetano Veloso’s autobiography Tropical Truth (Verdade Tropical in Portuguese) is a wide-ranging intellectual tour-de-force of a book that will make anyone a smarter Brazilianist. Some reviewers have said it is hard to understand for an American audience, but if you read Brutality Garden first you will have the background to understand the artistic movements that Caetano writes about from a more personal and revealing angle.

I too became interested in Tropicalia after studying Portuguese. I’m particular fond of Caetano Veloso and have read all the books you recommend here–actually, I’m only halfway through “Verdade Tropical” in Portuguese, having read it in English 5 years ago. Enjoy your studies.

Thanks Kathy! I’m still reading through Tropical Truth and enjoying it immensely.

Hello Lauren

I found your analyses of Tropicalia’s songs really interesting and, of course, it was a good surprise finding an website in english with such theme.

Just one comment: when you translate “palavrão” the real meaning is not “command” (or “big word” – aumentativo) but swear word.

Thanks

Thanks Fernando, and right you are about my translation — I fixed it in the post.

Just stumbled on this excellent rabbit hole earlier today (thanks, from the future!). Have listened to this album sooo many times and for some reason, the lines and the emotion grabbed me differently today.

But later this evening “Como Nossos Pais” came on shuffle and my ears caught on:

“por isso, cuidado, meu bem

ha perigo na esquina

(eles venceram, e o sinal ta fechado pra nos que somos jovens)”

I thought about how surely Elis would have heard Gal sing this song, and couldn’t possibly not be acknowledging it in some way… They seem to have traveled fairly different paths, but I was fascinated to learn that they were born only a few months apart in 1945 (on almost opposite sides of the country).

Elis Regina’s song definitely goes somewhere different (especially emotionally), but I do think there are some aligned themes. Anyway – a cool moment of pattern finding, and just wanted to share!