Being here in Bahía, working as part of a large team, has made me realize how much of my past language study was really a solitary endeavor, cut off from the living language. At home, I feel starved of exposure to Portuguese. There is Spanish everywhere in LA of course, and about 20 other languages that are widely spoken, yet aside from a handful of Brazilian-owned stores, you never hear Portuguese. Two or three times I have been in a hotel lobby somewhere in the US, and suddenly my ears perk up at the sound of a familiar but unexpected language. Is that–? It’s like spotting a diamond laying in the middle of the street.

(In a strange way, this rarity has developed a kind of nascent Brazilian identity, because whenever I do hear Portuguese my first thought is invariably, Ooh, someone is speaking my language! I have to go talk to them!)

Not having easy access to the language means I’ve had to actively seek out native speakers, radio stations, television programs, videos, conversation groups, all through the Internet, which is often a tiresome process. Because of the effort involved, I don’t get the daily exposure that is so crucial for internalizing the grammar.

But suddenly here I am in Bahía, and I feel like a sponge, just soaking in all the ambient language and sucking up as much as I can. Road signs, billboards, radio chatter, overheard conversations, tv shows – everything is potential Input. Even when I’ve had a difficult

day, from time to time I mentally smack myself and remind myself where I am and how incredibly lucky I am to be here, what with this convergence of my professional and personal interests. Soon I’ll be back at home and it will all be English and Spanish and Russian and Mandarin; there will be no more ocean, no more conversations over moquecas and caipirinhas, no more Portuguese everywhere I look.

I often think of how far I’ve come in just three years. It does feel as though I am well over the hump, where most of the hard work of studying and memorization has been done, and now I am just integrating, to use a psychiatrist’s word. My vocabulary is large enough that it now seems like a manageable task to fill in the gaps, instead of the overwhelming Herculean effort that it felt like to build up a vocabulary from scratch. If I don’t know a word, I can usually describe it well enough using other words plus gestures plus context. I know all my verb conjugations, even the irregular and weird ones, even in the imperfect and present and future subjunctives. In fact when it comes to all the major points of grammar that you find in your average textbook, I sort of feel like “Been there, done that, not much more to be gained.”

There is still a difference between intellectually knowing the grammar and feeling the grammar, having it right there on the tip of your tongue instead of locked up somewhere in your brain, where it takes too long to access. I have a lot of work yet to do to facilitate that

brain-to-tongue transfer, and the only way to do that is immersion and daily conversational practice. But it’s coming along.

The really tough part is that, despite all this, I still feel so far from where I want to be. I still experience the frustration of not being able to understand some people, all the more frustrating because this time it really matters that I understand them. And it is maddeningly inconsistent. With many of my colleagues from São Paulo, especially women, they speak slowly with lots of intonation and cadence, and I understand them beautifully. With others, I can at least get the gist of what they’re saying. But with some people, especially Bahians who speak very fast and clipped, it almost sounds like a different language. I pick up bits of phrases and isolated words, but I can’t put them all together. (At least in this I’m not alone, as some of the paulistas have confided to me that even they have trouble understanding Bahians).

This is a tough stage to be in as a language learner, because there is no clear path forward to overcoming these obstacles. You are out there adrift on the open sea, and though you can no longer see the continent you departed from behind you, neither can you see any trace of land ahead of you. You’re well beyond the scope of most language courses, books, and classes. There are almost no resources out there to guide you. I assume that this is the point where you just go live in Brazil or Portugal or wherever for a year or two, and you eventually become fluent through immersion. But what if you don’t have that option? Is there any other way to reach fluency?

There must be, because there are so many Brazilians who have never lived in an English speaking country, who studied English for just two or three or four years in school, and who speak beautiful fluent English – still with an accent, but otherwise fluent. Then again, are

these two situated really the same? It’s true that English is a difficult language to pronounce, and there are a lot of idioms and phrasal verbs to learn, but the basic grammar is pretty dirt simple compared to the Romance languages. There are only two verb conjugations, no grammatical genders, hardly any subjunctives, etc. Portuguese, on the other hand, is fairly simple to pronounce. Yes, it is not as phonetic as Spanish or Italian, but once you learn a few rules it mostly falls into place. The grammar, though, is ridiculous, even compared to other Romance languages, and even given the Brazilian tendency to avoid the more complicated constructions.

I’ve noticed – to generalize wildly – that even when Brazilian English speakers have an excellent command of the language, they still speak with a thick accent. I’m in the opposite situation. Not that I’m the best person to judge such things, but I think my pronunciation is pretty good. I get compliments on it all the time (many from people who are surprised / amused that I speak with a carioca accent). But my command of the language and grammar is far worse and has required a lot of effort to master.

Then there is the fact that, from what I can tell, Brazilians are exposed to English language media all the time. Half the shows on tv here in Salvador are American programs that have been subtitled or (shudder) dubbed. Go to any cinema and you will find American movies.

Turn on the radio and you hear American pop music. Drive down the street and you see billboards with English slogans. Even the language itself is embedded with hundreds of English loan words – shopping, drinque, rock, website, fast food, bar. So maybe it’s easier for Brazilians to become fluent in English without leaving the country.

Back to my original question – where to go from here? One of the few resources I have found that is still invaluable to me at this stage of my learning is a book – and it’s one I have endorsed a dozen times here on Hacking Portuguese – called Modern Brazilian Portuguese

Grammar (MBPG), by John Whitlam. This is a book that, every time I open it, makes me

realize how deep down the rabbit hole the language goes, far far beyond my basic command of the grammar. It illuminates this whole other grammar through the looking glass, the grammar of how people actually speak in their day to day lives. You could call it ‘deep grammar’ (and yes, this phrase is already used by linguists in an entirely different way, but I like the phrase so I’m stealing it anyway). And it makes me wonder why we teach languages in this backwards way, where first you learn the really formal, “proper” way to say things, then perhaps you learn a more casual way, then eventually through immersion you learn how most native speakers actually say it. Why not just teach the everyday language first?

I’ll give an example. When I first learned how to make a request in Portuguese, like ordering at a restaurant, I learned to use the conditional tense, like this:

Eu gostaria de pedir a feijoada, por favor. (I’d like to order the feijoada, please)

Or perhaps,

Você poderia me trazer mais um copo? (Would you bring me one more glass?)

Much later, I learned that the conditional tense sounds very formal in most situations, and it’s more common to use the imperfect instead, and that you could also leave out the subject você and the indirect object me:

Podia trazer mais um copo? (Could you bring one more glass?)

or even just

Trazia mais um copo?

Now, there’s nothing wrong with using any of these phrases. But when I listen to how my Brazilian colleagues actually order at a restaurant, here is what they say 90% of the time:

Cê traz mais um copo? (literally, You bring one more glass?)

Whaaat? They use the regular old present indicative tense? And they phrase it as if it were a statement…rather than a request? Doesn’t that sound bossy or rude? Well, I guess not, because even John Whitlam points out in MBPG that this is an extremely common way of making informal, spontaneous requests. Você me dá um guardanapo? This is how so much of everyday Portuguese is – short, to the point, free of any awkward grammatical encumbrances. This economy is one of the things I love most about the Brazilian language.

Of course, it’s good to teach people – especially new visitors to a country – how to say things as politely and graciously as possible. And a good dose of deference and politeness goes a long way when you are in the awkward stage of learning a new language and miscommunication is bound to occur. But I have found that, even in a business context, the vast majority of my conversations in Portuguese are extremely casual. I can’t even remember the last time I used A senhora or O senhor. Yet this is how Pimsleur – to take one example – teaches you to speak from the get-go. And very few courses at all will teach you that você often gets shortened to just cê, or deixa eu ver becomes chô ver, or onde está becomes cadê. There is this whole other dimension of the language that no one ever explicitly teaches you. So you end up learning the language in reverse, asymptotically approaching the colloquial dialect as you go along.

Here’s another example of deep grammar from MBPG. I had long been confused by when you use the imperfect vs the preterit with certain verbs like querer and saber. I never knew which form to use when I wanted to say something like “I always wanted to visit Salvador” or “I never knew that.”

Browsing through MBPG one day, I discovered that Mr. Whitlam had anticipated this difficulty – of course – and provided a tidy explanation that not only answers the question but illuminates a subtle layer of meaning that might have gone unnoticed.

Take querer for example. If you are talking about something that you used to want, and that want was later fulfilled, then you use the preterit:

Como criança, eu sempre quis visitar Salvador. (As a child, I always wanted to visit Salvador [and now here I am!])

It’s like your state of wanting has an upper bound in time – at some point, you got what you wanted and the want ended. The tense that you use for events that are complete and bounded in time is the preterit, so logically, eu quis is the right choice.

Now, say the want is still unfulfilled. Or maybe it was fulfilled, but say you are focusing on a period of time in the past when it wasn’t yet. Then you use the imperfect:

Como criança, eu queria visitar Salvador. (As a child, I wanted to visit Salvador [but I hadn’t yet/but I never did])

[In the comments, Yanna points out that Eu sempre queria sounds strange, while Eu sempre quis sounds fine. Apparently you can only use sempre with the preterit tense.]

Brilliant. Working every day in a fantastic binational team on a very complex project, I have found myself turning often to MBPG’s Practical Communications Guide for guidance. For example, I had noticed that when I needed to ask someone to do something, I was always using the same phrases – “Podia fazer isso?” or “Dá para fazer aquilo?” So I finally decided to take a look at the chapter on Making Requests, where Whitlam gives a whole range of different options, a few of which were new to me. I learned a very nice way of saying “Would you mind doing such and such?”, which I now use all the time:

Você se importa de destrancar o portão? (Would you mind unlocking the gate?)

So the way I am using this book currently is by browsing through a few chapters each week, just whatever interests me, and writing down any new or useful expressions that I think I might actually use. I review the expressions every couple days, just to keep them fresh in my memory, and during the day I look for opportunities to use them. As long as I take the time to write them down, review them periodically, and then actually use them, I’m finding that they stay in my long-term memory. (The very act of writing something down, by hand, is a proven way to help yourself remember it).

I think there is still a lot I could learn by just methodically going through this book and doing all the exercises in the companion workbook. And in the meantime, I need to find a way to use the language more often when I’m at home, to have more conversations and more immersion.

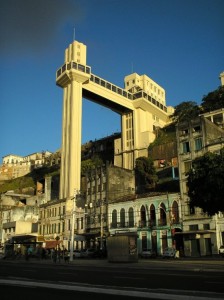

After weeks of anticipation, I’m finally in Salvador! E aqui é tudo beleza. This is my first trip to Brazil on business, and I’m finding that working in a bilingual, binational team is incredibly exciting, but it does come with its own frustrations as we adjust to the pace and ways of doing things in Brazil (the project unfolds in slow motion, as everything takes at least twice as long).

After weeks of anticipation, I’m finally in Salvador! E aqui é tudo beleza. This is my first trip to Brazil on business, and I’m finding that working in a bilingual, binational team is incredibly exciting, but it does come with its own frustrations as we adjust to the pace and ways of doing things in Brazil (the project unfolds in slow motion, as everything takes at least twice as long).